Where stakeholders align prior to INC-2

The first Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee (INC-1) required that the Secretariat develop a document outlining proposed elements for a final agreement ahead of INC-2. The document will be influenced by feedback received at the INC-1 as well as additional feedback collected from open submissions from observer individuals and states.

January 31, the INC-1 Chair heard from dozens of cross-sector representatives providing insights on what should be included in a legally-binding global plastic treaty.

Common themes

Most speakers referenced “waste hierarchy,” “precautionary principle,” and “polluter pays principle,” terms now common in negotiation parlance.

The Waste Hierarchy prioritizes prevention, reduction, and reuse over other measures, particularly recycling.

The Precautionary Principle asserts that the treaty must have an overarching objective to protect human health and the environment from the adverse impacts of plastic pollution.

The Polluter Pays Principle requires the parties responsible for producing plastics pollution pay for the damage done to people and the environment.

To read more about the three principles, click here.

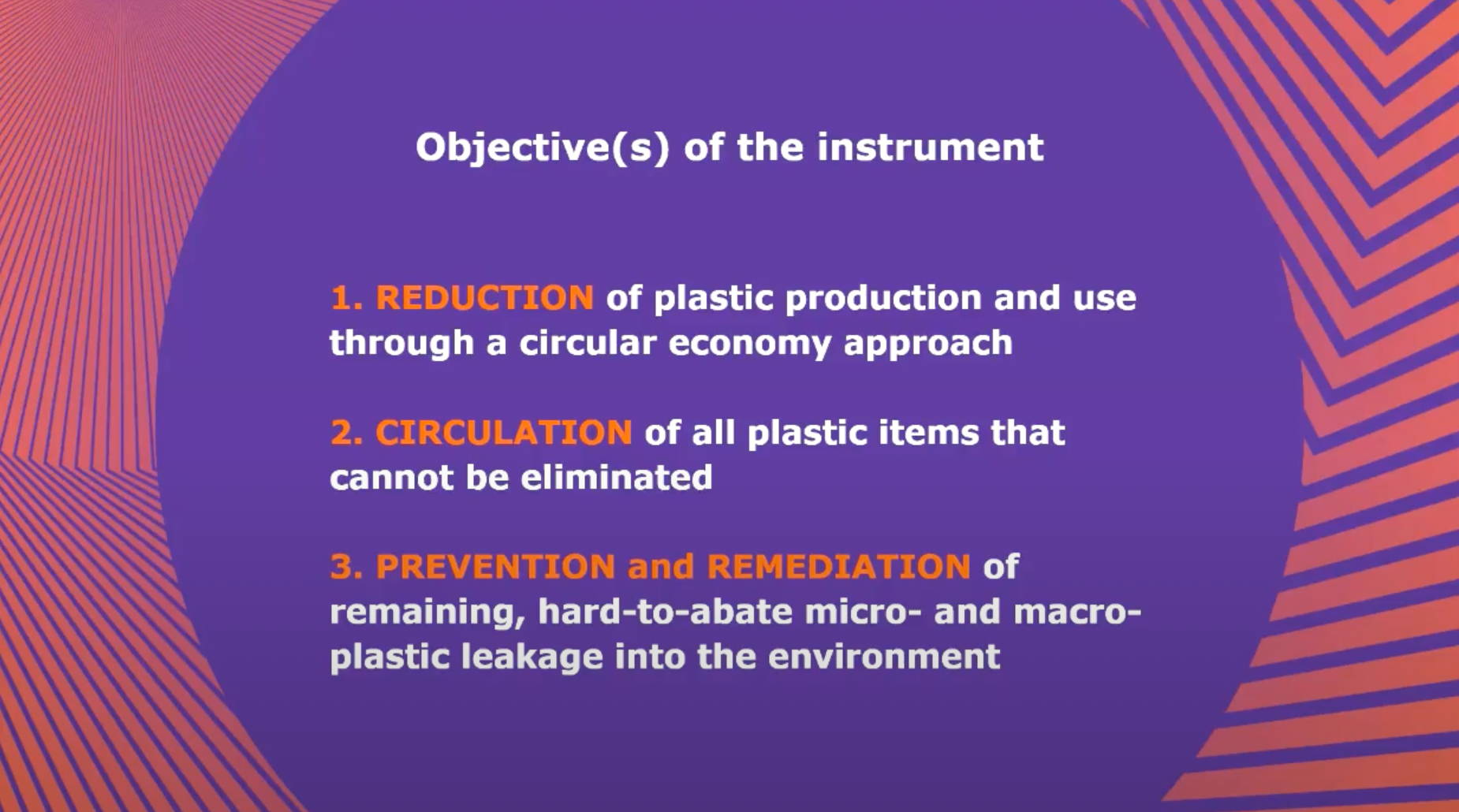

The Environmental Investigation Agency (EIA) summed up the majority of stakeholder’s input with submission of what the organization believes are the bare-minimum requirements for an effective treaty:

Core obligations and control measures:

- Sustainable sourcing of raw materials

- Sustainable polymer production and use

- Safe, sustainable plastic design and use

- Environmentally sound management of plastic waste

- Remediation of legacy plastic in the environment

- Transparency

- Dedicated programs of work to reduce consumption and waste in specific sectors

Implementation measures:

- National action plans

- National reporting

- Monitoring

- Subsidiary bodies

- Implementation committee

- Non-party provisions

Means of implementation:

- Effective financing mechanisms

- Capacity-building and technical assistance

- Technology transfer

Provisions with the most stakeholder alignment include:

- Phase outs and phase downs of problematic plastics and chemicals used in plastics production

- Prohibitions of plastic use in specific applications

- Creation of a trust fund financed by producers

- Assessments to understand progress and impacts of policy mechanisms

- Stringent government and business accountability

- Harmonized monitoring and transparency

- Closing trade loopholes

- Eliminating incineration and other burn technologies

- Reporting enforcement

- Robust financing systems to ensure all have the means of obligating the treaty

“Because of international trade, we need governments to agree on legally binding global rules,” said Jodie Roussell from the Business Coalition for a Global Plastics Treaty. “This will prevent a disconnected pathwork of national action plans, which is the context that our businesses operate under today.”

The treaty discussions have evolved significantly since last year’s UNEA 5.2, with focus shifting on a just transition, health and climate impacts of plastics, indigenous rights and representation, and mitigation of legacy plastics in the environment.

“This is becoming a brewing economic problem with consequences that are hard to fathom,” said Dr. João Ribeiro-Bidaoui of The Ocean Cleanup. “The future of our ocean and the species that call it home rests upon our ability to take immediate action against the legacy plastic pollution that threatens to engulf it.”

Dr. João Ribeiro-Bidaoui | The Ocean Cleanup

Gary Cohen of Healthcare Without Harm said health should be a fundamental design principle in crafting the treaty. Understanding health consequences requires looking across the entire plastics lifecycle, including materials that are used to produce and dispose of plastic and plastic waste. What’s more, Cohen urged the treaty to consider itself in the context of a broader set of tools used to address the climate crisis and dual emergencies of human and ecological health.

“The fossil fuel industry has identified petrochemical plastics as a major growth market and fossil fuel sink for continued oil drilling and gas fracking,” Cohen said. “If we do not restrict this expansion, plastics will become one of the major drivers for continued climate disruption on a planetary scale.”

The role of labor and a just transition

“In all stages of the lifecycle—from raw extraction of material to disposal and waste treatment—there are workers, and they need to be engaged and receive their place in the treaty,” said Bert De Wel from the International Trade Union Confederation. “This is necessary to have decent work for all, to guarantee social inclusion, and to aid in the eradication of poverty linked to the process.”

De Wel called for human and labor rights to be enshrined in the treaty mechanism, and that obligations to protect these rights be mandatory, not voluntary such as nationally determined contributions similar to the Paris Climate Accord.

Christina Jäger of the Yunus Environment Hub urged the treaty to integrate the informal sector into waste management systems in a systematic way that provides living wages and opportunities for improvement.

“It will be very important that multiple voices are heard and that there is an inclusive angle to this approach,” said Kristin Hughes of the World Economic Forum’s Global Plastic Action Partnership.

Kristin Hughes | World Economic Forum’s Global Plastic Action Partnership

The Action on Smoking and Health (ASH) and the Global Alliance for Incinerator Alternatives (GAIA) recommended that petrochemical producers be excluded from policymaking.

“The companies responsible for creating the problem should not be considered as stakeholders equal to those organizations that are trying to stop it,” said Laurent Huber on behalf of ASH. “It is crucial to identify inherent conflicts of interest and avoid them interfering in policy making.”

Nonetheless, industries with a vested interest in plastic production are at the negotiating table.

“We support an international agreement to eliminate plastic pollution while also enabling progress toward a net-zero emissions and achieving the SDGs,” said Stewart Harris on behalf of the International Council of Chemical Association (ICCA). “Plastic producers recognize the importance of sustainable production and consumption in addition to downstream measures to address the issue of plastic pollution.”

ICCA supports five key elements for a global framework:

- Government commitment to eliminating leakage and establishing national action plans

- Standardized definitions and reporting

- Waste management capacity building

- Better product design

- Achieving climate goals

“We encourage member states and all stakeholders to deliver against a high ambition,” said Katherine Loatman of the International Council of Beverages Associations. “We need national flexibility to ensure that policies succeed locally, however, to drive real progress, we also support the implementation of global targets.”

The beverage industry, Loatman said, supports prioritizing recycled content and bottle-to-bottle reuse models, as well as reducing the use of certain problematic plastics and leveraging existing recycling platforms as the basis for continued progress.

All written submissions to the Secretariat can be viewed here. INC-2 will be held in Paris with a tentative date of May 27, 2023. Draft text of an agreement is not expected before INC-3 in November of next year.